The forgotten referendum

Francesco Bastagli / International Herald Tribune

Published: November 24, 2006

MILAN: In a routine decision, the UN Security Council two weeks ago extended the mandate of the UN mission for the referendum in Western Sahara until April 30, 2007. When it was established in 1991, the mission was supposed to organize a referendum within nine months for the self-determination of the Saharawi people.

When Spain relinquished control of Western Sahara in 1975, the United Nations had already recognized it as a non-self-governing territory entitled to the guarantees provided by the UN Charter, including the right to self-determination.

However, in November of that year King Hassan II of Morocco moved to fill the vacuum left by Spain. A "green march" of tens of thousands of Moroccans crossed the border into Western Sahara to stake Moroccan sovereignty. This led to a prolonged conflict with the pro-independence Polisario Front. In 1991, the two parties agreed to a cease-fire to be followed by a referendum. The subsequent deadlock has been due to Morocco's refusal to allow any referendum that may lead to Western Sahara's independence.

To this date, most of Western Sahara is controlled by Morocco. Some 100,000 Saharawi refugees lead a miserable life in the Algerian desert. A 1,700-kilometer wall separates 130,000 Moroccan troops from Polisario forces that have nominal control over a swath of land bordering Algeria and Mauritania. UN military observers monitor the 1991 cease-fire.

When Spain relinquished control of Western Sahara in 1975, the United Nations had already recognized it as a non-self-governing territory entitled to the guarantees provided by the UN Charter, including the right to self-determination.

However, in November of that year King Hassan II of Morocco moved to fill the vacuum left by Spain. A "green march" of tens of thousands of Moroccans crossed the border into Western Sahara to stake Moroccan sovereignty. This led to a prolonged conflict with the pro-independence Polisario Front. In 1991, the two parties agreed to a cease-fire to be followed by a referendum. The subsequent deadlock has been due to Morocco's refusal to allow any referendum that may lead to Western Sahara's independence.

To this date, most of Western Sahara is controlled by Morocco. Some 100,000 Saharawi refugees lead a miserable life in the Algerian desert. A 1,700-kilometer wall separates 130,000 Moroccan troops from Polisario forces that have nominal control over a swath of land bordering Algeria and Mauritania. UN military observers monitor the 1991 cease-fire.

Through the years, Morocco has strengthened its hold over Western Sahara. Moroccan settlers now constitute the majority of the population. The natural resources of the territory, which under the UN Charter should be used for the sole benefit of the Saharawi people, are being exploited by Morocco.

A recent agreement between Morocco and the European Union gave European fishing fleets access to Western Saharan waters, among the richest in the world. Only Sweden spoke against it.

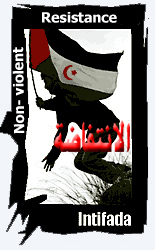

Since November 2005, there has been an ebb and flow of unrest in the territory. Morocco's response has been harsh. Men, women and children have suffered beatings, arbitrary arrests and detentions.

Polisario has so far refrained from challenging Morocco openly. It has also kept a distance from militant Islamist groups active in the region. However, discontent is growing. Disenfranchised and frustrated by the political stalemate, younger generations may turn to violence.

Last month the belt conveying phosphate from the Boukraa mine to the Laayoune port was blown up in the same location where Polisario launched its armed struggle against Spain in 1973.

Following the failure of past UN efforts, the UN secretary general is now proposing to hold direct negotiations between Morocco and Polisario without preconditions. This rather unimaginative approach will not break the deadlock without the engagement of international actors.

The United States has been sitting on the fence since 2004, when a settlement plan by former Secretary of State James Baker was rejected by Morocco. America should renew its interest in Western Sahara.

The Maghreb is a region of strategic importance, not the least for its abundant natural resources. Western Sahara may soon become an oil producer. From Algeria to Mauritania, however, the political and security environment is extremely fragile. Observers agree that the region will not stabilize until the Western Sahara issue is resolved.

France, which has the lead in the European Union on Western Sahara, is a stalwart champion of Morocco. It should use its privileged relationship to advocate a more courageous and innovative stand. As permanent members of the Security Council, the United States and France should join forces to prompt the Council into robust action.

Western Sahara has remained at the periphery of the international agenda for too long. Acting with the Council, the new secretary general could secure progress in the early stages of his mandate. Failure to do so may soon bring Western Sahara and its surrounding region to the front pages for all the wrong reasons.

Francesco Bastagli, a veteran of 32 years with the United Nations, served as the special representative of the UN secretary general for Western Sahara.

A recent agreement between Morocco and the European Union gave European fishing fleets access to Western Saharan waters, among the richest in the world. Only Sweden spoke against it.

Since November 2005, there has been an ebb and flow of unrest in the territory. Morocco's response has been harsh. Men, women and children have suffered beatings, arbitrary arrests and detentions.

Polisario has so far refrained from challenging Morocco openly. It has also kept a distance from militant Islamist groups active in the region. However, discontent is growing. Disenfranchised and frustrated by the political stalemate, younger generations may turn to violence.

Last month the belt conveying phosphate from the Boukraa mine to the Laayoune port was blown up in the same location where Polisario launched its armed struggle against Spain in 1973.

Following the failure of past UN efforts, the UN secretary general is now proposing to hold direct negotiations between Morocco and Polisario without preconditions. This rather unimaginative approach will not break the deadlock without the engagement of international actors.

The United States has been sitting on the fence since 2004, when a settlement plan by former Secretary of State James Baker was rejected by Morocco. America should renew its interest in Western Sahara.

The Maghreb is a region of strategic importance, not the least for its abundant natural resources. Western Sahara may soon become an oil producer. From Algeria to Mauritania, however, the political and security environment is extremely fragile. Observers agree that the region will not stabilize until the Western Sahara issue is resolved.

France, which has the lead in the European Union on Western Sahara, is a stalwart champion of Morocco. It should use its privileged relationship to advocate a more courageous and innovative stand. As permanent members of the Security Council, the United States and France should join forces to prompt the Council into robust action.

Western Sahara has remained at the periphery of the international agenda for too long. Acting with the Council, the new secretary general could secure progress in the early stages of his mandate. Failure to do so may soon bring Western Sahara and its surrounding region to the front pages for all the wrong reasons.

Francesco Bastagli, a veteran of 32 years with the United Nations, served as the special representative of the UN secretary general for Western Sahara.

0 Comments:

Enregistrer un commentaire

<< Home